All the impulses of life which I have described as building the interpenetrating worlds come forth from the Third Aspect of the Deity. Hence in the Christian scheme that Aspect is called "the Giver of Life", the Spirit who brooded over the face of the waters of space. In Theosophical literature these impulses are usually taken as a whole, and called the First Outpouring.

When the worlds had been prepared to this extent, and most of the chemical elements already existed, the Second Outpouring of life took place, and this came from the Second Aspect of the Deity. It brought with it the power of combination. In all the worlds it found existing what may be thought of as elements corresponding to those worlds. It proceeded to combine those elements into organisms which it then ensouled, and in this way it built up the seven kingdoms of Nature. Theosophy recognizes seven kingdoms, because it regards man as separate from the animal kingdom and it takes into account several stages of evolution which are unseen by the physical eye, and gives to them the mediæval name of "elemental kingdoms".

The divine Life pours itself into matter from above, and its whole course may be thought of in two stages—the gradual assumption of grosser and grosser matter, and then the gradual casting off again of the vehicles which have been assumed. The earliest level upon which its vehicles can be scientifically observed is the mental—the fifth counting from the finer to the grosser, the first on which there are separated globes. In practical study it is found convenient to divide this mental world into two parts, which we call the higher and the lower according to the degree of density of their matter. The higher consists of the three finer subdivisions of mental matter; the lower part of the other four.

When the outpouring reaches the higher mental world it draws together the ethereal elements there, combines them into what at that level correspond to substances and of these substances builds forms which it inhabits. We call this the first elemental kingdom.

After a long period of evolution through different forms at that level, the wave of life, which is all the time pressing steadily downwards, learns to identify itself so fully with those forms that, instead of occupying them and withdrawing from them periodically, it is able to hold them permanently and make them part of itself, so that now from that level it can proceed to the temporary occupation of forms at a still lower level. When it reaches this stage we call it the second elemental kingdom, the ensouling life of which resides upon the higher mental levels, while the vehicles through which it manifests are on the lower.

After another vast period of similar length, it is found that the downward pressure has caused this process to repeat itself; once more the life has identified itself with its forms, and has taken up its residence upon the lower mental levels, so that it is capable of ensouling bodies in the astral world. At this stage we call it the third elemental kingdom.

We speak of all these forms as finer or grosser relatively to one another, but all of them are almost infinitely finer than any with which we are acquainted in the physical world. Each of these three is a kingdom of Nature, as varied in the manifestations of its different forms of life as is the animal or vegetable kingdom which we know. After a long period spent in ensouling the forms of the third of these elemental kingdoms it identifies itself with them in turn, and so is able to ensoul the etheric part of the mineral kingdom, and becomes the life which vivifies that—for there is a life in the mineral kingdom just as much as in the vegetable or the animal, although it is in conditions where it cannot manifest so freely. In the course of the mineral evolution the downward pressure causes it to identify itself in the same way with the etheric matter of the physical world, and from that to ensoul the denser matter of such minerals as are perceptible to our senses.

In the mineral kingdom we include not only what are usually called minerals, but also liquids, gases and many etheric substances the existence of which is unknown to western science. All the matter of which we know anything is living matter, and the life which it contains is always evolving. When it has reached the central point of the mineral stage the downward pressure ceases, and is replaced by an upward tendency; the outbreathing has ceased and the indrawing has begun.

When mineral evolution is completed, the life has withdrawn itself again into the astral world, but bearing with it all the results obtained through its experiences in the physical. At this stage it ensouls vegetable forms, and begins to show itself much more clearly as what we commonly call life—plant-life of all kinds; and at a yet later stage of its development it leaves the vegetable kingdom and ensouls the animal kingdom. The attainment of this level is the sign that it has withdrawn itself still further, and is now working from the lower mental world. In order to work in physical matter from that mental world it must operate through the intervening astral matter; and that astral matter is now no longer part of the garment of the group-soul as a whole, but is the individual astral body of the animal concerned, as will be later explained.

In each of these kingdoms it not only passes a period of time which is to our ideas almost incredibly long, but it also goes through a definite course of evolution, beginning from the lower manifestations of that kingdom and ending with the highest. In the vegetable kingdom, for example, the life-force might commence its career by occupying grasses or mosses and end it by ensouling magnificent forest trees. In the animal kingdom it might commence with mosquitoes or with animalculæ, and might end with the finest specimens of the mammalia.

The whole process is one of steady evolution from lower forms to higher, from the simpler to the more complex. But what is evolving is not primarily the form, but the life within it. The forms also evolve and grow better as time passes; but this is in order that they may be appropriate vehicles for more and more advanced waves of life. When the life has reached the highest level possible in the animal kingdom, it may then pass on into the human kingdom, under conditions which will presently be explained.

The outpouring leaves one kingdom and passes to another, so that if we had to deal with only one wave of this outpouring we could have in existence only one kingdom at a time. But the Deity sends out a constant succession of these waves, so that at any given time we find a number of them simultaneously in operation. We ourselves represent one such wave; but we find evolving alongside us another wave which ensouls the animal kingdom—a wave which came out from the Deity one stage later than we did. We find also the vegetable kingdom, which represents a third wave, and the mineral kingdom, which represents a fourth; and occultists know of the existence all round us of three elemental kingdoms, which represent the fifth, sixth and seventh waves. All these, however, are successive ripples of the same great outpouring from the Second Aspect of the Deity.

We have here, then, a scheme of evolution in which the divine Life involves itself more and more deeply in matter, in order that through that matter it may receive vibrations which could not otherwise affect it—impacts from without, which by degrees arouse within it rates of undulation corresponding to their own, so that it learns to respond to them. Later on it learns of itself to generate these rates of undulation, and so becomes a being possessed of spiritual powers.

We may presume that when this outpouring of life originally came forth from the Deity, at some level altogether beyond our power of cognition, it may perhaps have been homogeneous; but when it first comes within practical cognizance, when it is itself in the intuitional world, but is ensouling bodies made of the matter of the higher mental world, it is already not one huge world-soul but many souls. Let us suppose a homogeneous outpouring, which may be considered as one vast soul, at one end of the scale; at the other, when humanity is reached, we find that one vast soul broken up into millions of the comparatively little souls of individual men. At any stage between these two extremes we find an intermediate condition, the immense world-soul already subdivided, but not to the utmost limit of possible subdivision.

Each man is a soul, but not each animal or each plant. Man, as a soul, can manifest through only one body at a time in the physical world, whereas one animal soul manifests simultaneously through a number of animal bodies, one plant soul through a number of separate plants. A lion, for example, is not a permanently separate entity in the same way as a man is. When the man dies—that is, when he as a soul lays aside his physical body—he remains himself exactly as he was before, an entity separate from all other entities. When the lion dies, that which has been the separate soul of him is poured back into the mass from which it came—a mass which is at the same time providing the souls for many other lions. To such a mass we give the name of "group-soul".

To such a group-soul is attached a considerable number of lion bodies—let us say a hundred. Each of those bodies while it lives has its hundredth part of the group-soul attached to it, and for the time being this is apparently quite separate, so that the lion is as much an individual during his physical life as the man; but he is not a permanent individual. When he dies the soul of him flows back into the group-soul to which it belongs, and that identical lion-soul cannot be separated again from the group.

A useful analogy may help comprehension. Imagine the group-soul to be represented by the water in a bucket, and the hundred lion bodies by a hundred tumblers. As each tumbler is dipped into the bucket it takes out from it a tumblerful of water (the separate soul). That water for the time being takes the shape of the vehicle which it fills, and is temporarily separate from the water which remains in the bucket, and from the water in the other tumblers.

Now put into each of the hundred tumblers some kind of colouring matter or some kind of flavouring. That will represent the qualities developed by its experiences in the separate soul of the lion during its lifetime. Pour back the water from the tumbler into the bucket; that represents the death of the lion. The colouring matter or the flavouring will be distributed through the whole of the water in the bucket, but will be a much fainter colouring, a much less pronounced flavour when thus distributed than it was when confined in one tumbler. The qualities developed by the experience of one lion attached to that group-soul are therefore shared by the entire group-soul, but in a much lower degree.

We may take out another tumblerful of water from that bucket, but we can never again get exactly the same tumblerful after it has once been mingled with the rest. Every tumblerful taken from that bucket in the future will contain some traces of the colouring or flavouring put into each tumbler whose contents have been returned to the bucket. Just so the qualities developed by the experience of a single lion will become the common property of all lions who are in the future to be born from that group-soul, though in a lesser degree than that in which they existed in the individual lion who developed them.

That is the explanation of inherited instincts; that is why the duckling which has been hatched by a hen takes to the water instantly without needing to be shown how to swim; why the chicken just out of its shell will cower at the shadow of a hawk; why a bird which has been artificially hatched, and has never seen a nest, nevertheless knows how to make one, and makes it according to the traditions of its kind.

Lower down in the scale of animal life enormous numbers of bodies are attached to a single group-soul—countless millions, for example, in the case of some of the smaller insects; but as we rise in the animal kingdom the number of bodies attached to a single group-soul becomes smaller and smaller, and therefore the differences between individuals become greater.

Thus the group-souls gradually break up. Returning to the symbol of the bucket, as tumbler after tumbler of water is withdrawn from it, tinted with some sort of colouring matter and returned to it, the whole bucketful of water gradually becomes richer in colour. Suppose that by imperceptible degrees a kind of vertical film forms itself across the centre of the bucket, and gradually solidifies itself into a division, so that we have now a right half and a left half to the bucket, and each tumblerful of water which is taken out is returned always to the same section from which it came.

Then presently a difference will be set up, and the liquid in one half of the bucket will no longer be the same as that in the other. We have then practically two buckets, and when this stage is reached in a group-soul it splits into two, as a cell separates by fission. In this way, as the experience grows ever richer, the group-souls grow smaller but more numerous, until at the highest point we arrive at man with his single individual soul, which no longer returns into a group, but remains always separate.

One of the life-waves is vivifying the whole of a kingdom; but not every group-soul in that life-wave will pass through the whole of that kingdom from the bottom to the top. If in the vegetable kingdom a certain group-soul has ensouled forest trees, when it passes on into the animal kingdom it will omit all the lower stages—that is, it will never inhabit insects or reptiles, but will begin at once at the level of the lower mammalia. The insects and reptiles will be vivified by group-souls which have for some reason left the vegetable kingdom at a much lower level than the forest tree. In the same way the group-soul which has reached the highest levels of the animal kingdom will not individualize into primitive savages, but into men of somewhat higher type, the primitive savages being recruited from group-souls which have left the animal kingdom at a lower level.

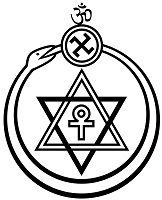

Group-souls at any level or at all levels arrange themselves into seven great types, according to the Minister of the Deity through whom their life has poured forth. These types are clearly distinguishable in all the kingdoms, and the successive forms taken by any one of them form a connected series, so that animals, vegetables, minerals and the varieties of the elemental creatures may all be arranged into seven great groups, and the life coming along one of those lines will not diverge into any of the others.

No detailed list has yet been made of the animals, plants or minerals from this point of view; but it is certain that the life which is found ensouling a mineral of a particular type will never vivify a mineral of any other type than its own, though within that type it may vary. When it passes on to the vegetable and animal kingdoms it will inhabit vegetables and animals of that type and of no other; and when it eventually reaches humanity it will individualize into men of that type and of no other.

The method of individualization is the raising of the soul of a particular animal to a level so much higher than that attained by its group-soul that it can no longer return to the latter. This cannot be done with any animal, but only with those whose brain is developed to a certain level, and the method usually adopted to acquire such mental development is to bring the animal into close contact with man. Individualization, therefore, is possible only for domestic animals, and only for certain kinds even of those. At the head of each of the seven types stands one kind of domestic animal—the dog for one, the cat for another, the elephant for a third, the monkey for a fourth, and so on. The wild animals can all be arranged on seven lines leading up to the domestic animals; for example, the fox and the wolf are obviously on the same line with the dog, while the lion, the tiger and the leopard equally obviously lead up to the domestic cat; so that the group-soul animating a hundred lions mentioned some time ago might at a later stage of its evolution have divided into, let us say, five group-souls each animating twenty cats.

The life-wave spends a long period of time in each kingdom; we are now only a little past the middle of such an æon, and consequently the conditions are not favourable for the achievement of that individualization which normally comes only at the end of a period. Rare instances of such attainment may occasionally be observed on the part of some animal much in advance of the average. Close association with man is necessary to produce this result. The animal if kindly treated develops devoted affection for his human friend, and also unfolds his intellectual powers in trying to understand that friend and to anticipate his wishes. In addition to this, the emotions and the thoughts of the man act constantly upon those of the animal, and tend to raise him to a higher level both emotionally and intellectually. Under favourable circumstances this development may proceed so far as to raise the animal altogether out of touch with the group to which he belongs, so that his fragment of a group-soul becomes capable of responding to the outpouring which comes from the First Aspect of the Deity.

For this final outpouring is not like the others, a mighty outrush affecting thousands or millions simultaneously; it comes to each one individually as that one is ready to receive it. This outpouring has already descended as far as the intuitional world; but it comes no farther than that until this upward leap is made by the soul of the animal from below; but when that happens this Third Outpouring leaps down to meet it, and in the higher mental world is formed an ego, a permanent individuality—permanent, that is, until, far later in his evolution, the man transcends it and reaches back to the divine unity from which he came. To make this ego, the fragment of the group-soul (which has hitherto played the part always of ensouling force) becomes in its turn a vehicle, and is itself ensouled by that divine Spark which has fallen into it from on high. That Spark may be said to have been hovering in the monadic world over the group-soul through the whole of its previous evolution, unable to effect a junction with it until its corresponding fragment in the group-soul had developed sufficiently to permit it. It is this breaking away from the rest of the group-soul and developing a separate ego which marks the distinction between the highest animal and the lowest man.